The early records inform us that between AD 705 and 712, a Cyninges tun, (m. king’s farm or manor), was established at Wimborne by King Ine. At about the same time, his sister, Cuthberga, founded a religious community there and, to provide it with protection and the necessary construction and agricultural labour and requirements, the Cyninges tun became the administrative centre for this part of Wessex.

By the time of Domesday Book, in 1086, it had grown into a highly productive unit of over 45,000 acres (18,210 ha). Throughout the centuries that followed, it remained as a royal manor, but leased to the most powerful and influential baronial families of the realm, from the earls of Leicester and Lincoln, to the dukes of Somerset and Lancaster. Following the upheavals of the so called 'English Anarchy' during the reign of King Steven (r. 1135-54), the great manor of Kyngeston was confiscated when Robert de Beaumont, 4th Earl of Leicester, rebelled against the Crown. However, within the passing of a year, Earl Robert was again received back into the royal favour and, shortly afterwards, he began the construction of a new manor house and its manorial complex in what is now, Kingston Lacy Park. The manorial records show that his wife, Lauretta, came to live here during the 1170’s, in what was called her curia, or main house.

Many of the details and descriptions of this complex of buildings, as well as the continuous extensive alterations and repairs, came to light in the accounts and documents of the manorial records that were discovered hidden away in the muniment rooms in Kingston Lacy House, mostly unseen for many generations. Like photographic snap-shots that might have been taken six or seven hundred years ago, these remarkable documents enable us today to clearly understand the everyday running of the manor, its sustainability and financial accounts, as well as the lives, duties and incomes of the tenants and people themselves.

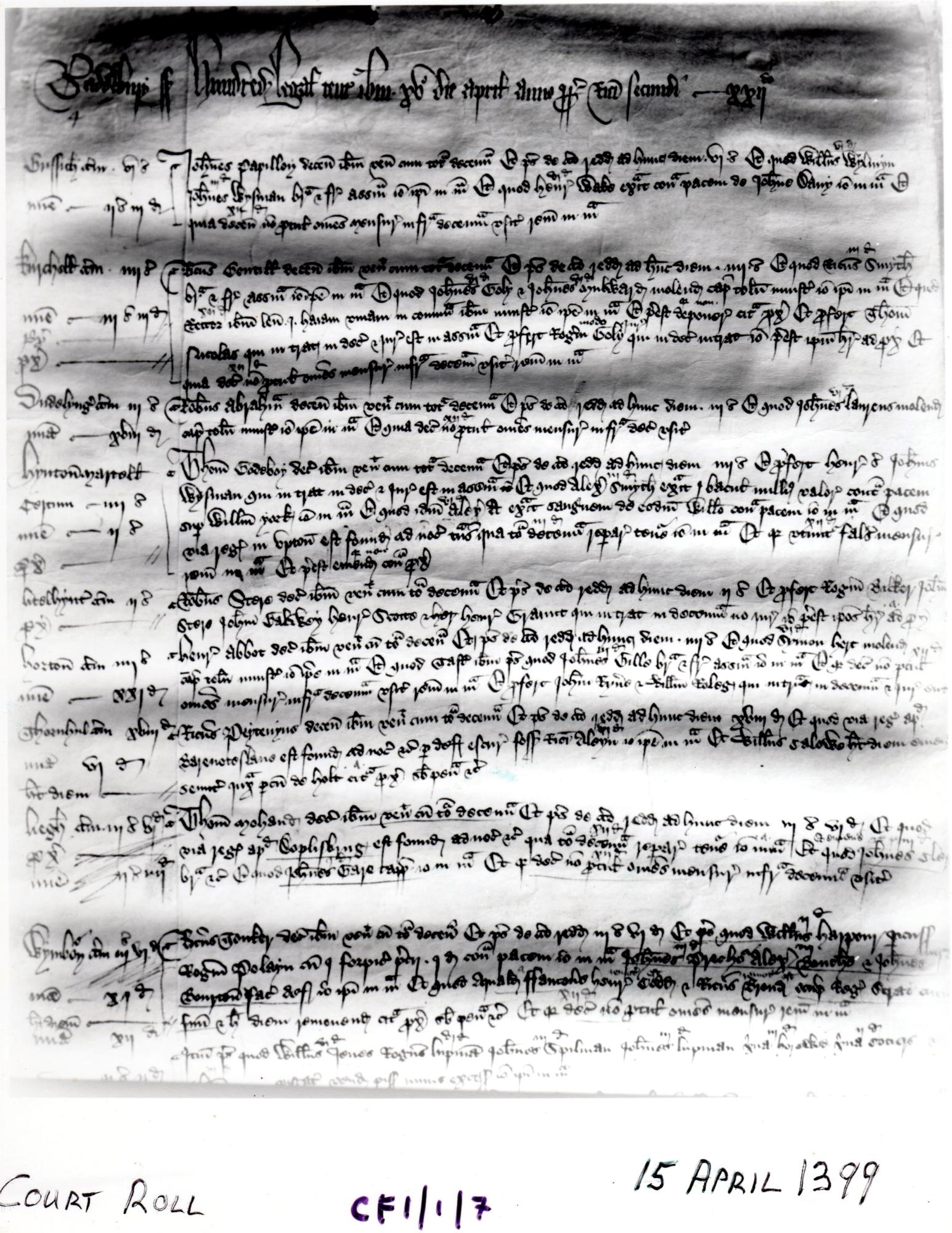

The Court Roll for the manor recorded on 15th April 1399. The document records each village on the left-hand side along with the rents and court fines. The writing on the right-hand side records what had happened since the previous court meeting. The open-air court was held on the Moot six times each year; the four Quarter Days and two for the View of Frankpledge, a system where everyone was responsible and accountable for each other. The manor moot still survives today and was a large banked enclosure in the form of a square. Here, the people of the manor assembled, with a judicial seat for the lord of the manor, a place for the Homage (jury), as well as a punishment place (e.g. a pillory or stocks) and a pond (punishment of ducking).

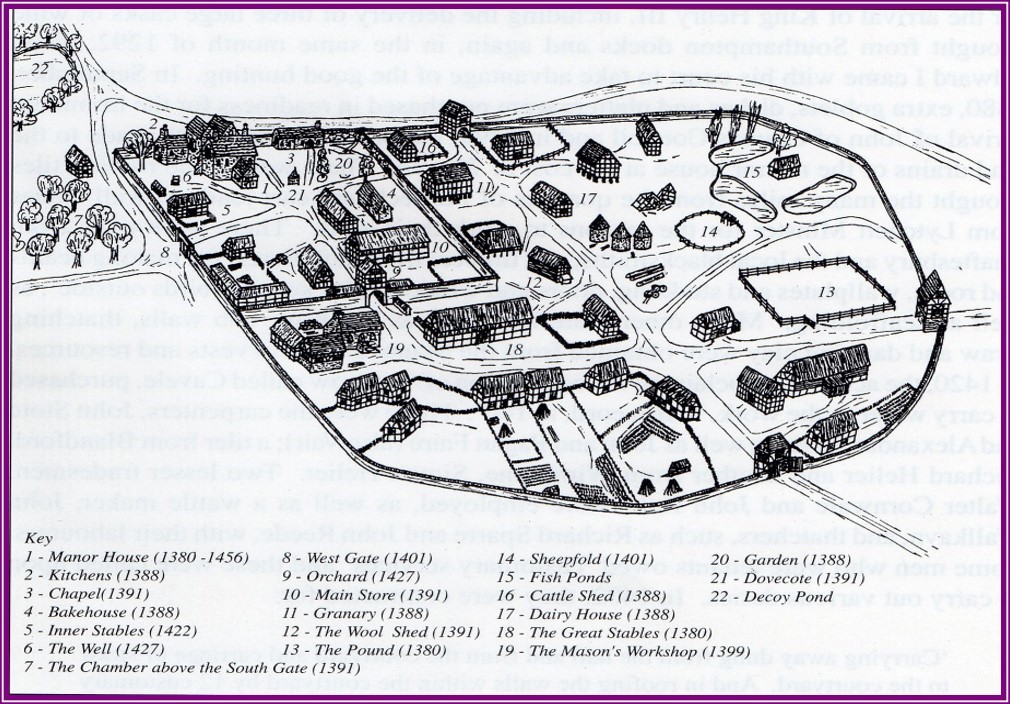

The main manor house and its associated complex of buildings lay 4 miles north of Wimborne, adjacent to the old roadway to Blandford, known as the ‘Wimborne Way’. The site has been located in the Park, just to the north of the present Kingston Lacy House. By the early 1300’s, the complex was divided into two areas, or Courts, containing about sixty-five main constructions and covering an area of about 35 acres (14 ha). The Inner Court was surrounded by a high defensive wall with two gated entrances. Within it lay the huge double-aisled manor house and stables, a counting house, large kitchens and storerooms, a dove house, a private chapel and a walled garden. The Outer Court contained the working areas, including stables, cattle and sheep sheds, builder’s yards, store rooms, servant’s living quarters, as well as workshops for the carpenters, blacksmiths, coopers and masons.

Close by were extensive ponds used for wild-fouling and to maintain stocks of fresh fish for the household. There were also specially constructed warrens in the surrounding woodlands where rabbits were 'farmed', to provide fresh everyday meat for the table. Surrounding and to the north of the manor house was a deer park of 600 acres (243 ha) enclosed by a deep double ditch and palisade fence, where, officially, only the King and his Court were able to hunt the specially kept deer. Stretching away to the north and east was an open hunting chase, noted in 1311 as being 21 miles in length and 6 miles in width, which equates to about 84,000 acres (33,993 ha). This afforded the lords of the manor and their guest’s excellent hunting and falconry. Riding over open and rough country, as well learning and practising the many skills used in hunting, often became the training ground for young esquires and knights in times of peace.

In terms of the manor house and its complex of buildings, walls were either constructed in Purbeck stone or locally obtained dark sandstone or, for lesser buildings, a framework of stout timbers infilled with wattle and daub. The latter was a worthy mixture of mud, clay, straw, cow dung and animal hair that was applied to both sides of a wattle frame. Windows and doorways were either made in stone or with oak that had been carefully selected and cut from the manorial Forest of Holt. Roofs were either thatched with wheat straw or were stone tiled depending on the position or importance of the individual building. For example, the original thatch of the manor house was replaced in 1332, when twenty drovers and their wagons and men were employed to haul stone tiles from the quarries in Purbeck – perhaps the first convoy in rural Dorset!

The meticulous details recorded so many centuries ago also enable us to glimpse the actual people of the manor; amongst them were Paganus Bolle, Richard Helier, Nicholas Brewer, Walter Frye, Christina Brownying, Walteer Gaye, Henry Garbe and Jayne Rideout. Amongst the various trades and skills that were required to administer, run and maintain it each year, there were builders, thatchers, woodsmen, wattle fence makers, shepherds and cowmen. In the hose itself, there were overseers to maintain control, chamber and household staff, as well as cooks and ‘slaves of the kitchen’. Although 'common' labour was plentiful, especially before 1348 and the tragedy and upheavals that followed the Black Death, specialist trades, such as masons, were brought in from elsewhere. These men and their colleagues could be easily paid for as this manor was important to the Crown’s Exchequer, both in the annual revenues, rents and expenses it earned, but also in the maintenance of the powerful baronial families who supported it.

Manorial records prove that by the early 14th century its extensive lands had increased to over 109,000 acres (44,110 ha). It extended from the River Stour in the west to the River Avon and Ringwood in the east, and from the sea shore in the south to almost Shaftesbury in the north. From the contemporary manorial records, we are able to estimate that the annual income in today’s value was in the region of £2.5 million. They also show us that before the Black Death in 1348, between 600 and 700 people lived as tenants on its lands and were therefore dependant upon it for their living and well-being.

Here a few examples from the manorial records:

20th day of April 1272. Item. That a letter of confirmation has been sent to the Master of Works for the requesting of a number of masons and builders to carry out necessary reparations to the curia house at Kingston and several of buildings there.

Item. That new trestles, benches and other boards are now made ready for their arrival.

27th day of June 1302. Item. That the master masons have built several new windows and doorways to the new chambers in the west part of the demesne house. That a new wall has been erected with fine worked corbyls. The supervisor Richarde Huntingdon has inspected the works and agreed.

4th day of October 1332. Item. That more stone tiles were brought from the quarries on Purbeck for roofing on the house and great hall and kitchens. The carters are each paid the agreed rates of 10s and fodder.

11th day of June 1407. Item. That John Brierly and Richard Webber have been sent from Kings Somborne to rectify the work made last year. The cost of the work is made at £2.11s.4d.

Manorial records also clearly prove that the more menial tasks were carried out by general labourers and simple builders who lived either in the villages and hamlets of the manor, or in the two local towns of Wimborne and Blandford. These men were usually paid 'in kind', by allowances of food, clothing or part of their homestead rents, the latter referred to as 'boon-work' and was calculated as between 1d. and 3d. per day. They worked from day-break to night-fall, between twelve to fourteen hours during the summer months when the majority of projects were carried out. Meal and rest breaks were limited to no more than two hours a day and these lengthy hours must have detracted from overall productivity. The problem lay not in medieval laziness, but in an understandable antipathy to drudgery. The tradesmen however, or specialists, such as tilers, carpenters and masons, worked much shorter hours and were brought in from elsewhere. They were paid set rates of actual money depending upon their skill or level of qualification, usually between 2s. and 3s. per week. This rate usually had to cover expensive tools, a maul cost 3d, a trowel 6d, a chisel 2d, and spades and shovels cost 2d. each. Craftsmen masons had usually to pay for the wages and tools of an assistant or apprentice who travelled from job to job with them. Interestingly, although the Duchy of Lancaster records that the payment rates at Kingston Lacy never seem to have altered during the Medieval and Tudor periods, obviously the value did as the penny or pound rose or fell – and so you could say that the rate reflected the value of the day, but surely must have made annual accounting much easier.

In terms of the masons, most worked directly for the Duchy of Lancaster. This afforded them almost continuous employment and gave them six rates of pay, ranging from 34d. per week for the most skilled and dropping by 2d. per rate to 24d. for the newly qualified. This was not unusual and as an example, at Caernarvon Castle in 1316 there were thirteen different rates. Duchy records also prove that a leading mason earned about £7.10s a year, and a middle-ranking mason who would have worked for nearly 300 days a year, earned about £5.10s. As a comparison, for a similar time period at Kingston Lacy, a carpenter would have earned about £4.10s., a Purbeck quarryman about £2.10s., and a 'common or garden' labourer about £1.11s. However, in respect of their role and responsibility, much higher rates were paid to the supervisors and overseers of the masonry works. These men were usually either employed directly by the lords of the manor or by the Duchy and their rates were calculated as being around 6s. per week. They were responsible for ensuring that the work was not only carried out in time, but to the highest standard. They awarded 'honours' to the men, signed the work payments and answered to the Controller of the Works.

The organisation and administration of the building works followed very strict procedures. For example, when masons were required to work on the manor, it was first necessary for an official request to be made to either the Crown Exchequer or Duchy officers, accompanied by a letter of confirmation that an extensive list of requirements could be properly and fully financially supported. This letter confirmed that the manor could meet their wages and expenses, provide suitable work areas, a required number of labourers, appropriate accommodation and also a suitable place to hold their meetings. The first reference to the latter at Kingston Lacy was in 1322 when it is recorded that, 'a separate meeting place should be set aside for the masons when they come to the repairs at the great manor house.' Once the letter of confirmation had been received and a date agreed for the commencement of work, men were dispatched to the quarries on the Isle of Purbeck to seek out and select the best stone and supervise it’s cutting and loading onto the drover’s wagons. Their responsibility was also to ensure that the stone was actually transported the 27 miles to Kingston Lacy, not only on time, but did not disappear en route.

Certainly, it is clear that the operative masons were employed in three levels of skill. The first and lower level were the under masons, men who could roughly prepare the stone. When it arrived, it was unloaded from the wagons and placed on large timbered work benches where it was formed into rough working blocks by either sawing or splitting. Once this was completed, large wooden mauls and metal chisels were used to 'further smooth and prepare the stone and render it fit for the hands of the more expert workman', the second level. This was the middle-ranking mason, a part qualified man who was skilled enough to form good work, such as walling blocks that were suitable for the construction of buildings. The third level was the mason craftsman, a fully qualified mason who had usually undergone several years of extensive training and worked directly for the Duchy of Lancaster. He could not only finely finish the stone, but could also carve it into wonderful designs or figures. In this part of the kingdom these craftsmen operated from the royal manor at King’s Somborne, near Winchester, undoubtedly chosen because it lay between the great ecclesiastical centres of Winchester, Salisbury and Sherborne and close to several extensive royal manors, including Kingston Lacy.

In our modern world of Health and Safety, Regulations at Work and Minimum Wage rates, it is often impossible to imagine the conditions that these craftsmen and labourers worked under. The work areas themselves were both busy and often dangerous places. Timber, stone and a multitude of materials were heavy, dusty and often had a mind of their own. Equipment was probably quite rural and injuries must have been commonplace, with no Social Security or sick pay to support a family at such a time, hardship and hunger were often experiences they had to contend with. And yet, the records reveal that at Kingston Lacy things were not as bad as the former might suggest. Because the tradesmen and craftsmen worked directly for the Duchy or the lord of the manor, they were often cared for in one way or another in the event of such problems. The lower grades and labourers, who were usually manorial tenants, were protected by their 'Customs', a set of regulations that ensured their survival in times of hardship. Their tenancies were also protected under a Copyhold agreement that ran for three lives; each time someone died, a new name was added to the agreement. Their rents, called Dues, were usually paid by labour and this could be deferred or paid by another member of the family if problems or illness arose. A case, we can presume, of the manor looking after its own.

Brethren, for all of this, the qualified mason, employed directly by the Duchy of Lancaster, was indeed a man of good standing and his arrival at Kingston Lacy must have been greeted by the locals with great awe and considerable regard. One might only imagine the stories he could have told, and the sights and the people he would have seen in his many travels throughout the country. Along with his colleagues he probably worked on the beautiful cathedrals at Winchester and Salisbury, or perhaps, one of the great royal palaces or monumental castles.

The mason was a true professional and really had 'the hands of a more expert workman'.

David Smith

Lodge of St Cuthberga No.622

Wimborne